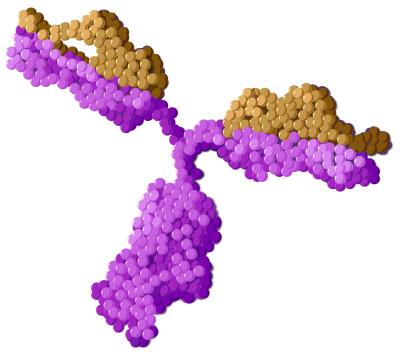

Illustration of an antibody, a three-pronged protein made by the immune system. When the immune system makes a type of antibody called immunoglobulin E (IgE) against a food allergen, it can lead to food allergy.

A food allergy develops when a person eats, touches or inhales a protein in food called an allergen, and then the immune system makes a type of antibody against the allergen called IgE. Copies of this IgE antibody move through the blood and attach to two kinds of cells in the immune system.

When a person with IgE antibodies eats, touches or inhales the same food allergen again, the allergen binds to the antibodies attached to the immune cells. This binding tells the cells to release huge amounts of chemicals. The chemicals cause different symptoms depending on the tissue where they are released. For instance, when they are released in the skin, they cause hives, itching and redness.

Scientists have many basic questions about food allergy. These include:

- Why do some people develop IgE antibodies to certain foods while other people do not?

- Why do some people who develop IgE antibodies to a food allergen have no allergic reaction?

- Why do some people with food allergy have severe allergic reactions, but not others?

Researchers are seeking answers to these questions with the hope of finding ways to prevent food allergies or make allergic reactions to food less severe.

Food Allergy Prevention

For several decades, health care experts advised parents to avoid giving infants foods that could cause food allergy. But in 2008, the American Academy of Pediatrics decided there was no convincing evidence that delaying giving such foods to infants older than 6 months could prevent food allergy. Finally, the 2015 results of a NIAID-funded study called Learning Early About Peanut Allergy (LEAP) led to a complete reversal of the old advice. The LEAP researchers found that giving children foods with peanut before their first birthday drastically reduced their risk for having peanut allergy by the time they were 5 years old. Peanut allergy developed 80 percent less frequently in children who had started eating peanut as infants than in children who had avoided eating peanut until age 5.

The LEAP researchers then asked many of the children in the study to avoid eating peanut from ages 5 to 6 years. Peanut allergy developed 74 percent less frequently among 6-year-olds whose early diet had included peanut than among 6-year-olds who had originally avoided peanut. This suggested that feeding an infant peanut prevents the development of peanut allergy in a strong, long-lasting way.

Next, the LEAP researchers tested whether the protection gained from early consumption of peanut products would last into adolescence if the children could choose to eat peanut in whatever amount and frequency they wanted. Those children who were allergic to peanut at age 6 were advised to continue avoiding it. The study team enrolled more than 500 of the original LEAP study participants when they were about 13 years old and tested them for peanut allergy. The tests showed that regular, early peanut consumption reduced the rate of peanut allergy in adolescence by 71% compared to early peanut avoidance. The findings were published in May 2024.

The LEAP study also suggested that developing peanut allergy depends on whether children first get exposed to peanut by eating it or through skin contact. Some infants in the group that avoided peanuts became sensitized to peanut at a young age. The researchers hypothesized that exposure to tiny amounts of peanut through the skin might have caused this sensitization.

Based on the strength of the LEAP results, NIAID led the development of the Addendum Guidelines for the Prevention of Peanut Allergy in the United States published in January 2017.

Since then, researchers around the world have conducted studies that found giving infants other allergy-causing foods such as milk and egg may also help prevent food allergy. As a result, many countries are expanding the original guidelines for preventing peanut allergy to include foods beyond peanut.

Scientific Advances

Introducing Peanut in Infancy Prevents Peanut Allergy into Adolescence

May 28, 2024Feeding children peanut products regularly from infancy to age 5 years reduced the rate of peanut allergy in adolescence by 71%, even when the children ate or avoided peanut products as desired for many years. These new findings, from a study sponsored and co-funded by the National Institutes of Health’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), provide conclusive evidence…