The Problem

Ticks can become infected with more than one disease-causing microbe (called co-infection). Co-infection may be a potential problem for humans, because the Ixodes ticks that transmit Borrelia burgdorferi, the bacterium which causes Lyme disease, often carry and transmit other pathogens, as well. In the United States, a single tick could make a person sick with any one—or more—of several diseases at the same time. Possible co-infections include Lyme borreliosis, anaplasmosis, babesiosis, Powassan virus, and B. miyamotoi infection.

Nymphal and Adult Ticks Shown to be Co-Infected: Studies To Understand Potential Relation to Human Disease Underway

Studies have looked at co-infection rates at different points in the tick’s life cycle. In a comprehensive review of 61 different published reports, Nieto and Foley found that 2 to 5 percent of young nymphal I. scapularis ticks were reported to be co-infected with more than one microbe. Adult tick co-infection rates with B. burgdorferi varied widely between 1 to 28 percent across the reports analyzed (Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 9(1):93-101, 2009). Although humans are more likely to be bitten by the smaller nymphal stage ticks (CDC), co-infection rates in adult ticks may provide important information about how tickborne diseases are transmitted.

Co-infection by some or all of these other microbes may make it more difficult to diagnose Lyme disease. Being infected by more than one microbe might also affect how the immune system responds to B. burgdorferi . NIAID-supported studies of mice found that co-infection with human granulocytic ehrlichiosis—which is now known as anaplasmosis—results in more severe Lyme disease. Another study showed that when mice were co-infected with Babesia microti and B. burgdorferi, the presence of Babesia also enhanced the severity of Lyme disease, while the presence of B. burgdorferi appeared to limit the effects of Babesia.

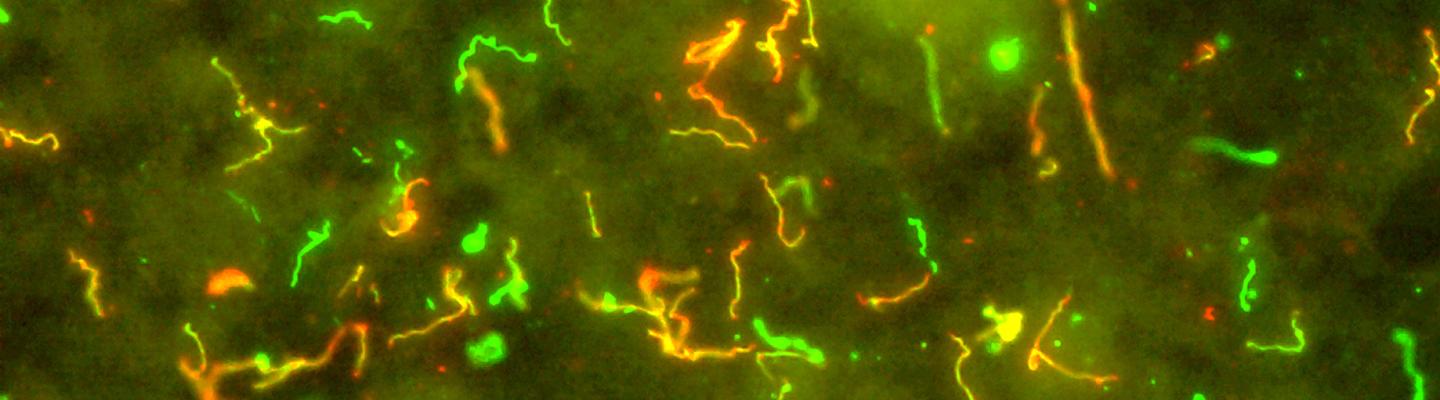

Another study looked at the tissues of mice infected with both B. burgdorferi and Anaplasma phagocytophilium, the bacterium that causes anaplasmosis in humans. Scientists found increased numbers of B. burgdorferi in the ears, heart, and skin of co-infected mice; however, the numbers of A. phagocytophilium remained relatively constant. The co-infected mice produced fewer antibodies for A. phagocytophilium but not for B. burgdorferi. These findings suggest that co-infection can affect the amount of microbes in the body and antibody responses.

Clinical Studies

In NIAID-supported clinical studies on Lyme disease, patients with persisting symptoms were examined to determine if they might have been co-infected with other tickborne infectious diseases at the time of their acute episode of Lyme disease. In one clinical study, babesioisis (B. microti), granulocytic ehrlichiosis (Anaplasma phagocytophilia), and tickborne encephalitis virus infection were evaluated. The study found that 2.5 percent of blood samples showed signs of B. microti and 8.6 percent had evidence of A. phagocytophilia. None of the patients examined were found to be positive for tickborne encephalitis viruses. In this study, the persistence of symptoms in the vast majority of patients with "post-Lyme syndrome" could not be attributed to co-infection with one of these microbes.

B. miyamotoi, a bacterium that is related to the bacteria that causes tickborne relapsing fever, is known to be present in all tick species that transmit Lyme disease. In 2013, NIAID-supported investigators showed evidence of B. miyamotoi infection in the United States and studies to better understand this pathogen continue to be supported. One of these preliminary studies showed patients with acute Lyme disease were more likely to be co-infected with B. miyamotoi than people who did not have Lyme disease.

NIAID researchers are exploring ways to differentiate Lyme disease patients from patients of other look-alike diseases such as Southern Tick-Associated Rash Illness (STARI) . In addition, NIAID-funded researchers recently published on a multiplex serological platform that can simultaneously detect up to eight tick-borne diseases from a single patient sample at the point-of-care.

How co-infection might affect disease transmission and progression is not known but could be important in diagnosing and treating Lyme and other tickborne diseases. NIAID-supported projects continue to work toward better understanding the effects of co-infection.