Early Work Led to the Development of an Acellular Pertussis Vaccine

In the 1940s, a combination diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis vaccine was introduced. Known as DTwP, the vaccine contained diphtheria toxin, tetanus toxin, and whole (but killed) Bordetella pertussis bacteria. By the mid-1970s, however, due to adverse reactions attributed to the whole-cell vaccine, some patients and parents began to reject the vaccine despite continuing circulation of B. pertussis and pertussis disease. As vaccination rates went down, infection rates crept up. To address these issues, the National Institutes of Health held an international symposium to examine the risks and benefits of whole-cell pertussis vaccination in November 1978.

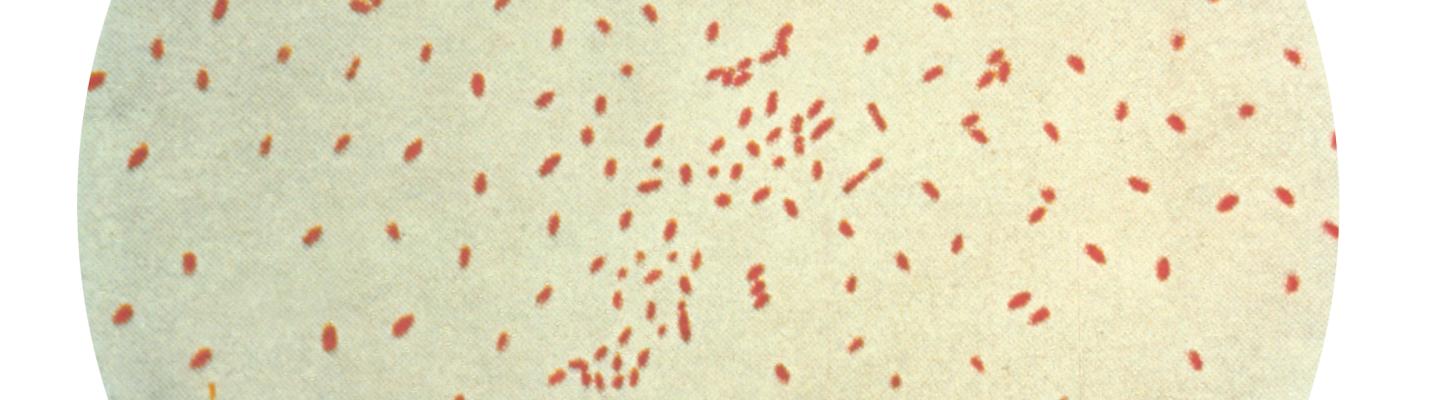

Bordetella pertussis bacteria cause pertussis disease.

Around the same time, scientists at NIAID and elsewhere began exploring alternatives to the whole-cell vaccine—in particular acellular vaccines, which would use only selected portions of B. pertussis to stimulate an immune system response. In the 1970s and 1980s, John J. “Jack” Muñoz and his colleagues at NIAID Rocky Mountain Laboratories made key discoveries about these bacterial components and their role in inducing immunity to pertussis. In 1986, Dr. Muñoz’s group successfully isolated and characterized a fragment of B. pertussis DNA containing the genes for pertussis toxin, the substance responsible for establishing infection, and mapped these genes within the bacterial genome.

By the late 1980s, researchers in Japan had begun evaluating candidate acellular vaccines, and NIAID was asked to accelerate the development and testing of these candidates with the eventual goal of Food and Drug Administration (FDA) licensure. Through its network of Vaccine and Treatment Evaluation Units (VTEUs), NIAID organized a multicenter clinical trial to evaluate 13 candidate acellular vaccines for safety and ability to generate an immune response. Follow-up trials, also sponsored by NIAID, showed that acellular vaccines protected children from pertussis and were associated with fewer side effects, and led to the 1996 licensure and use of the first diphtheria-tetanus-acellular pertussis (DTaP) vaccine in the United States. Today, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends the DTaP vaccine for infants and children.

Animal and Human Studies Improve Vaccines and Vaccine Regimens

In June 2012, NIAID- and FDA-funded researchers at FDA published research describing the first-ever animal model of pertussis disease. In baboons, infection is acquired naturally, and signs and symptoms mimic human illness. In the wake of rising pertussis rates, FDA researchers more recently reported using the baboon model to assess the effectiveness of acellular pertussis vaccines. Their results suggested that while the acellular vaccine was effective in preventing severe disease among vaccinated animals, it did not prevent vaccinated animals from carrying the infection or passing it on to other animals. These findings, which may help explain the recent increases in pertussis cases in the United States and elsewhere, were published in November 2013.

CDC recommends that infants receive their first dose of pertussis vaccine at two months of age. Because infants younger than two months have high rates of infection, CDC recommended that pregnant mothers receive the vaccine to protect newborns before their first dose. In a clinical trial, the VTEUs evaluated the safety of and immune system response to a dose of combination tetanus, diphtheria and pertussis vaccine (Tdap) administered to pregnant women and women who had recently given birth. They found that the vaccine stimulated mothers to produce antibodies to pertussis and efficiently transfer them to their newborns. Another VTEU trial, focusing only on women who receive Tdap soon after giving birth, is currently evaluating participants’ immune system response to the vaccine and changes in their pertussis antibody levels over an extended period of time.