On this World Photo Day, we explore colorized microscopy images with NIAID microscopist John Bernbaum and visual specialist Julie Marquardt. Colorized images play a critical role in promoting public awareness of the NIAID mission and advancing scientific goals, allowing everyone from beginners to experts to not only see microscopic cells but also to understand their components and environment. Bernbaum and Marquardt describe how they create visually appealing, scientifically accurate photos of cells, viruses, and bacteria.

NIAID conducts and funds research on a wide range of infectious diseases, and each one has a distinctive appearance. Viruses and bacteria that cause disease infect cells differently and reproduce uniquely. Accurately identifying and presenting them visually requires an approach that is both precise and flexible. It often involves trial and error to find the best tools and effects for each visual presentation. Bernbaum and Marquardt collaborate closely in this meticulous process, selecting subjects and generating images in response to research priorities, current events, and public need. Another key focus is producing images related to disease topics for which there is a lack of publicly available images.

Bernbaum performs conventional electron microscopy in the NIAID Integrated Research Facility, using a transmission electron microscope (TEM) and a scanning electron microscope (SEM) to capture images of particles that have been preserved, inactivated, processed, and prepared for the microscope. For TEM, this involves embedding small sample pieces in plastic resin blocks, which get sectioned and stained for visibility. For SEM, preparation involves thin layered samples grown on or applied to flat surfaces, mounted on viewing stubs, and coated with specific metals for visibility.

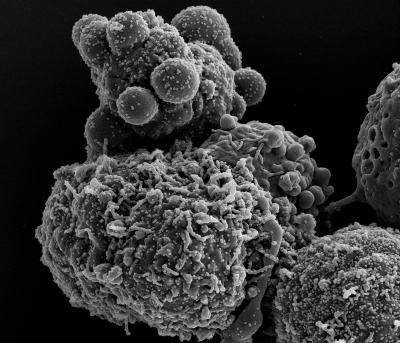

The microscopes have built-in digital camera systems, which can be adjusted for contrast, brightness, astigmatism, focus, shutter scan rate speeds, and resolution levels. This helps microscopists to capture the virus or bacterium in a complex cellular environment. The microscopy photographs are in black and white when Bernbaum hands them over to Marquardt. While experts can often understand the black-and-white image, adding color to the different components makes them clearer to a wider audience (and adds visual appeal!).

Novel Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 (Omicron) in black and white

Marquardt carefully studies the black-and-white photographs, adjusting the lighting, contrast, and black and white color balance. She may rotate or crop the images for best presentation and composition. Then she zooms in and hand selects the virus or bacterium particles and cell areas, taking great care to be accurate. She might apply basic high-contrast colors at this point to touch up selections. This can require many rounds of consultation and conversation between Marquardt and Bernbaum as they home in on the virus or bacterium.

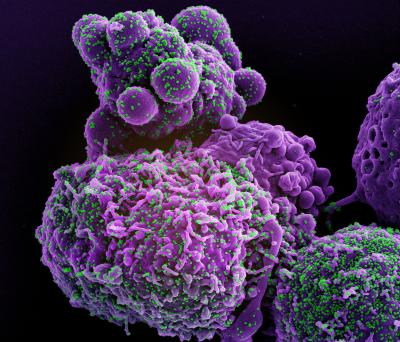

Once they have accurately selected the particles in the photograph, Marquardt starts to play with color. In this stage, she prioritizes aesthetic color combinations that offer sufficient contrast to distinguish particles from cell areas. She also experiments with color combinations that are unique from what is currently available. She applies effects and advanced techniques to make the images visually appealing and informative to diverse audiences.

Novel Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 (Omicron) colorized

The results of their collaborative work are scientifically accurate and visually stunning images, making them valuable resources to the research community and the public. As a government agency, NIAID is uniquely equipped to devote advanced skills and resources toward creating these images, which are freely available to reuse. To see and share NIAID colorized microscopy images, visit and bookmark the NIAID Flickr page, where new images are uploaded regularly and available for download in high-resolution format, free of cost.