NIAID Approach Highlighted in New Journal Supplement

A special Oct. 19 supplement to the Journal of Infectious Diseases contains nine articles intended as a summary of a National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID)-hosted pandemic preparedness workshop that featured scientific experts on viral families of pandemic concern. Sponsored by NIAID, the supplement features articles on 10 viral families with high pandemic potential known to infect people. Concluding the supplement is a commentary from NIAID staff on the “road ahead.”

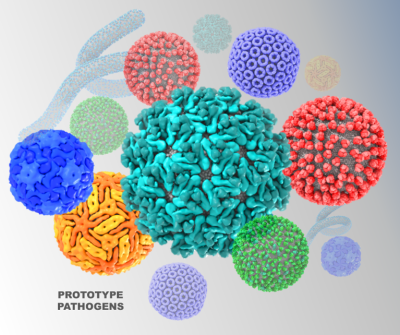

Many of the viruses in these 10 families have no vaccines or treatments licensed or in advanced development for use in people. Rather than facing the enormous task of developing medical countermeasures for individual viruses, one strategy is to use the “prototype pathogen” approach – which was shown to be successful with the rapid development of vaccines during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. This approach characterizes “representative” viruses within viral families so that knowledge gained, including medical countermeasures strategies, can be quickly adapted to other viruses in the same family.

The NIAID workshop on pandemic preparedness had several goals, including to describe the prototype pathogen approach, select prototype pathogens for future study, and identify knowledge gaps within the selected viral families. Prototype viruses being considered for study within the 10 families of pandemic concern are listed below. The ranges of these prototype viruses span the globe.

- Arenaviridae: These viruses are capable of spillover from animals to people and can lead to severe viral hemorrhagic fevers. Lassa virus and Junín virus were selected as prototypes.

- Bunyavirales, includes the Hantaviridae, Nairoviridae, Peribunyaviridae and Phenuivirdae families, among others. Viruses in this family are spread by several different arthropods (mosquitoes, ticks, midges) or rodents and can cause mild to severe symptoms and death.

- Phenuivirdae prototypes are Rift Valley fever virus, severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus (SFTSV), Toscana virus, and Punta Toro virus.

- Nairoviridae prototypes are Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus and Hazara virus.

- Hantaviridae prototypes are Hantaan virus, Sin Nombre virus, and Andes virus.

- Peribunyaviridae prototypes are La Crosse virus, Oropouche virus, and Cache Valley virus.

- Paramyxoviridae: This family includes highly transmissible viruses that are well known (measles, mumps) and more recently emerged (Nipah virus). Viruses proposed as prototypes are Cedar virus, canine distemper virus, human parainfluenza virus 1/3, and Menangle virus.

- Flaviviridae: These viruses, primarily transmitted by mosquitoes and ticks, are responsible for hundreds of millions of human infections worldwide each year. Viruses proposed as prototypes are West Nile virus, dengue serotype 2 virus, and tick-borne encephalitis virus.

- Togaviridae: Most of these viruses are spread by mosquitoes and cause disease in animals that then can spillover to people. Viruses proposed as prototypes are Chikungunya virus and Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus.

- Picornaviridae: This family includes common human viruses such as polio and hepatitis A, but new technology has led scientists to recently discover more than 300 new viruses. The four selected prototypes are enteroviruses A71 and D68, human rhinovirus C virus, and echovirus 29.

- Filoviridae: Filoviruses can cause severe hemorrhagic fever in people and have been causative agents of recent outbreaks. Ebola virus is the prototype virus.

Experts with careers built on knowledge of each virus family are leading research teams across the U.S., studying how viruses infect cells, which models of disease most closely mimic human disease, and how to use new technology when designing vaccines and treatments. NIAID leaders are anticipating that the prototype approach will create “opportunities for investigators from multiple fields or with specialized technical expertise to collaborate in new ways.”

Reference: Pandemic Preparedness at NIAID: Prototype Pathogen Approach to Accelerate Medical Countermeasures—Vaccines and Monoclonal Antibodies. Journal of Infectious Diseases (2023).