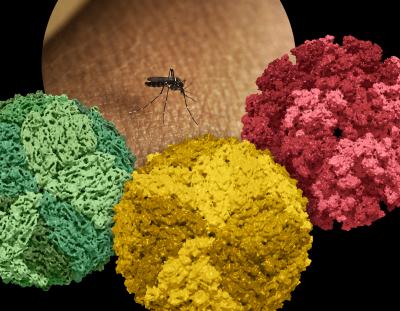

Mosquito-borne diseases include some of the most important human diseases worldwide, such as malaria and dengue. With global temperatures increasing because of climate change, mosquitoes and the pathogens they transmit are expanding their range. For example, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently reported a number of malaria and dengue cases transmitted within the United States in Texas and Florida. Therefore, it has become more urgent to understand the interactions between climate, mosquitoes, and the pathogens mosquitoes transmit to humans.

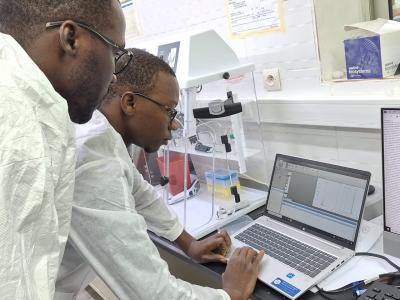

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) Climate Change and Health Initiative is a collaborative effort across NIH Institutes and Centers to reduce the public health impact of climate change. As part of the Initiative’s Scholars Program, NIH brings climate and health scientists from outside the U.S. federal government to work with NIH staff to share knowledge and help build expertise in the scientific domains outlined in the Initiative’s Strategic Framework.

Luis Chaves, Ph.D., is a 2023 Scholar working with NIAID. Dr. Chaves is an associate professor in the Department of Environmental and Occupational Health in the School of Public Health-Bloomington, Indiana University, and was previously an associate scientist at the Instituto Gorgas in Panama. His research focuses on understanding the impacts of environmental change on the ecology of insect vectors and the diseases they transmit. Over the last 20 years, he has combined field studies and modeling approaches, both statistical and mathematical, to address how insect vectors respond to changes in the environment and how these changes impact the transmission of diseases, such as malaria and dengue. NIAID spoke with Dr. Chaves about his work.

Note: responses to the questions have been edited for clarity and brevity.

In what ways have you seen climate changes impact vectors and disease transmission?

There is very strong evidence that climate change has affected vector-borne diseases. This includes mosquito-borne diseases, like malaria and dengue, but also other diseases like leishmaniasis, which is transmitted by sandflies. Changes in temperature and rainfall affect the spread of disease vectors and impact their breeding behavior. For example, there is evidence of the impact of El Niño weather events on malaria transmission. Higher temperatures and more rainfall make a more suitable habitat for mosquito breeding, causing an increase in disease transmission. In other areas, El Niño weather patterns are associated with droughts, which may reduce disease transmission but cause food shortages. These weather patterns have been known and studied before, but climate change has generated more extreme conditions resulting in more extreme weather events. So, we can see that there is robust evidence that climate change is having a massive impact on human health and wellbeing.

What sparked your interest in examining how socio-economic conditions impact vector-borne disease transmission and control?

I remember the first encounter I had with Chagas disease was visiting an uncle who lived in a rural setting. I was told not to visit a neighbor’s house because they had Chagas disease. There were lots of discussions about how his neighbor got Chagas because his home was made from mud, which is why kissing bugs, the vectors of Chagas disease, got inside. That was the first time I observed an increased prevalence of diseases in places with social exclusion and poverty. More generally, infectious diseases cannot be put out of the social and economic context where they emerge and are transmitted. If you have people with substandard housing, is that a choice, or a constraint because of the underlying socio-economic inequities? It is impossible to learn about the ecology of disease transmission without understanding that the ecology of transmission is not only ecological and environmental but also social.

What are the advantages of using mathematical modeling to study vector-borne diseases?

Mathematical and quantitative modeling have been incredibly useful to expand the ways in which the relations shaping disease patterns can be studied This ability to understand interactions advances our capacity to engage in more relational science, where factors aren’t understood as fixed and independent forces, but as dynamic and interdependent. Relations between variables can’t be described by a fixed constant proportion, but by nonlinearities that can be easily grasped by machine learning algorithms and other data science tools. Computers have made it easier to collect, process and analyze larger datasets. The automation of data assimilation using pipelines that integrate different data sources and algorithms can lead to robust “boosted” predictions about where and when to expect the transmission of some vector-borne diseases. Mathematical models also show how the stability of natural systems can collapse following small changes in the environment, and that has clear implications about why we need to worry as climate change continues its current course.

What limitations do you see in the use of data science?

Data science poses ethical dilemmas, because not everyone mining freely available data is likely to do so with altruistic aims, nor is it clear how communities and individuals could benefit from the data they generated when someone profits from that or how communities, and even individuals, are protected from potential misuse. I also think there is a need to always consider the context in which data are generated, as this approximation allows us to see what else is out there. The more nuanced our knowledge is, the more likely we can generate actionable knowledge that improves human health and wellbeing. That’s why it’s so important to include information on how data is collected (metadata) and how to use it. The nuances don’t come from just looking at the data. They require experience, observation, and immersion in nature to create a clearer picture of vector-borne disease transmission.

How has your work influenced vector control and prevention activities?

My research at the Costa Rican Institute for Research and Training in Nutrition and Health’s (INCIENSA) and the Costa Rican Vector Control Program was centered around developing insect vector maps and training people working in vector control about the impacts of climate change. This also involved evaluating past policies and their impact on parasitic and neglected tropical diseases. For example, comparing how different public health strategies like Mass Drug Administration versus vector control might impact malaria transmission and elimination. These activities increased the awareness about the importance of climate change, particularly among vector control inspectors, with whom I interacted closely on their work. My research has also supported a focus on Mass Drug Administration as a major tool to eliminate malaria in Costa Rica.

What impact do you hope your research will have?

I’ll be happy if my research can serve, at least, the communities where the research is being done. As long as my research can lead to diminishing transmission of infectious pathogens or reducing the populations of vectors, then I will be happy. If that eventually leads to the elimination of those diseases, I’ll be even happier. I want to be able to provide resources for the local communities, so they can understand health problems or health threats within their local environment. For example, one of the nicest experiences I have had as a researcher was in Panama, where at least three or four studies on leishmaniasis have been done in the same community. In that community, we have seen how people come up with their own solutions, partly based on what they learn from when you did research in that location. You see how they modify their houses and look for changes in incidence of new cases. When they tell you that cases of leishmaniasis have gone down, that newborns and children aren´t getting the disease, that is very fulfilling.