Powerful Sequencing Tool Helps Identify Infectious Diseases in Mali

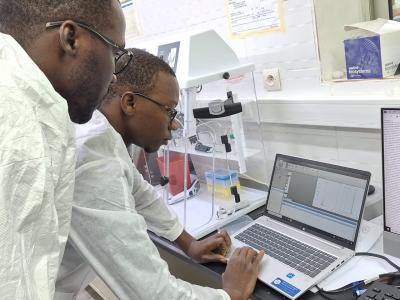

An advanced diagnostic tool used in an observational clinical study in Bamako, Mali, helped identify infectious viruses in hospital patients that normally would have required many traditional tests. Scientists, led by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), designed the study to help physicians identify the causes of unexplained fever in patients and to bring awareness to new technology in a resource-limited region.

Because malaria is the most common fever-causing illness in rural sub-Saharan Africa, most medical workers in the region presume patients with a fever have malaria. But recent NIAID work has identified dengue, Zika and chikungunya viruses – like malaria, all spread by mosquitos – in some Malian residents.

The observational study of 108 patients, published recently in The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, added the advanced diagnostic test, known as VirCapSeq-VERT, to traditional testing methods to identify cases of measles, SARS-CoV-2, HIV, and other viral diseases in patients. Surprisingly, more than 40% of patients were found to have more than one infection.

VirCapSeq-VERT is the virome capture-sequencing platform for vertebrate viruses, a powerful DNA sequencing technique capable of finding all viruses known to infect humans and animals in specimens, such as plasma. VirCapSeq-VERT uses special probes that capture all virus DNA and RNA in a specimen, even if the researcher does not know which specific virus to look for. Scientists then sequence the captured DNA and RNA to identify viruses present to solve the mystery of which viral infection(s) a patient has.

In the study, the researchers recommend that combining VirCapSeq-VERT with traditional diagnostic tests could greatly assist physicians “in settings with large disease burdens or high rates of coinfections and may lead to better outcomes for patients.”

Scientists from NIAID’s Division of Clinical Research collaborated on the project from July 2020 to October 2022 with colleagues from the University of Sciences, Techniques, and Technologies of Bamako, Mali, and Columbia University.

Reference: A Koné, et al. Adding Virome Capture Metagenomic Sequencing to Conventional Laboratory Testing Increases Unknown Fever Etiology Determination in Bamako, Mali. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene DOI: https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.24-0449 (2024).