In 1917, when the United States entered the European war, Kinyoun had been largely forgotten by the public, but the “Kinyoun portable bed disinfectors” (for bedding, clothing, dressings, and for killing lice) he had coinvented were still being used for sterilization in newly built Army hospitals. Always quietly patriotic—and in uniform throughout most of his adult life—Kinyoun now sought to join the Army. Old friends rallied around him. Somehow, at age 57, he was given an active duty commission as an expert epidemiologist assigned to the beloved region of his birth, the cantonments in North and South Carolina. Perhaps an old Bellevue colleague, now Army Surgeon General Gorgas, had pulled some strings. Kinyoun was working in the places he loved best, directly under Gorgas and one of his senior staff officers, Colonel Victor C. Vaughan (1851–1929), another bacteriologist friend stationed in North Carolina, to investigate statewide typhoid epidemics. Four months after deployment, Kinyoun found a lump in his neck; biopsy revealed an inoperable lymphosarcoma, a fatal diagnosis. Vaughan helped him circumvent Army regulations to get the best civilian care available; Welch, also now on active duty as a Brigadier General, may have arranged for his treatment at Johns Hopkins Hospital.

Kinyoun still carried the old rabbit’s foot (25), but it no longer brought him luck. On 15 August 1918, he drafted both a will and a letter of instruction to Lizzie that upon his death he be buried with their daughter Bettie, who had died of diphtheria—by now both a vaccine-preventable and a serum-curable disease—30 years earlier. As his health declined, Kinyoun, apparently under the protection of Army medical friends, was reassigned on 6 December 1918 as a pathologist to Washington’s Army Medical Museum, where his late friend Walter Reed had been curator, and finally, one day before his death, to Surgeon General Gorgas’ office. Kinyoun died at home of “myocardial insufficiency” (primary death certificate diagnosis), with Lizzie at his side, and the Army physician caring for him, Captain George C. Smith, in attendance, at 4:45 p.m. on Valentine’s Day, 14 February 1919. He was by that time forgotten by all but a few old timers. Lizzie died in 1948, and the couple was reunited in a single Centerview gravesite with their daughter Bettie.

Along with others of the 116,707 fallen American soldiers of the Great War, Kinyoun’s name was placed within the cornerstone of the World War I Memorial on the National Mall in Washington, DC. A marble statue to World War I’s fallen District of Columbia employees, with Kinyoun’s name engraved upon it, sits largely unnoticed in a stairwell of the District’s Municipal Building on Pennsylvania Avenue, not far from the White House. Kinyoun’s second son, Conrad Houx Kinyoun (1896–1948), became a medical scientist who worked for a time at the NIH, married into the North Carolina Craighill family of noted Rockefeller scientist Rebecca Lancefield (1895–1981), and became Director of Savannah, Georgia’s, Department of Health Laboratories. The Liberty Ship Joseph J. Kinyoun (a cargo ship) was commissioned and saw service in World War II, but later was destroyed. In 1935, Wilfred H. Kellogg, one of the nation’s leading plague experts, recalled: “I remember of Dr. Kinyoun… there was no better bacteriologist probably in the country” (106). Kinyoun’s name, Kellogg claimed, “should be indelible in the annals of public health” (55). Lizzie and her oldest surviving daughter, Alice Eccles Kinyoun [Houts] (1889–1974; Figure 22), who had always believed that one day the stigma of San Francisco would fade and that Kinyoun would at last be fully vindicated, put 75 boxes of his papers, documents, photographs, and memorabilia into storage, where those surviving have remained untouched for almost a century (18).

![Kinyoun’s eldest surviving daughter, Alice Eccles Kinyoun [Houts] (right), and her grandson Joseph Kinyoun Houts, Jr. (left), 1971.](/sites/default/files/styles/image_style_original/public/KinyounFigure22.jpg?itok=5Nx80ufj)

Kinyoun’s eldest surviving daughter, Alice Eccles Kinyoun [Houts] (right), and her grandson Joseph Kinyoun Houts, Jr. (left), 1971.

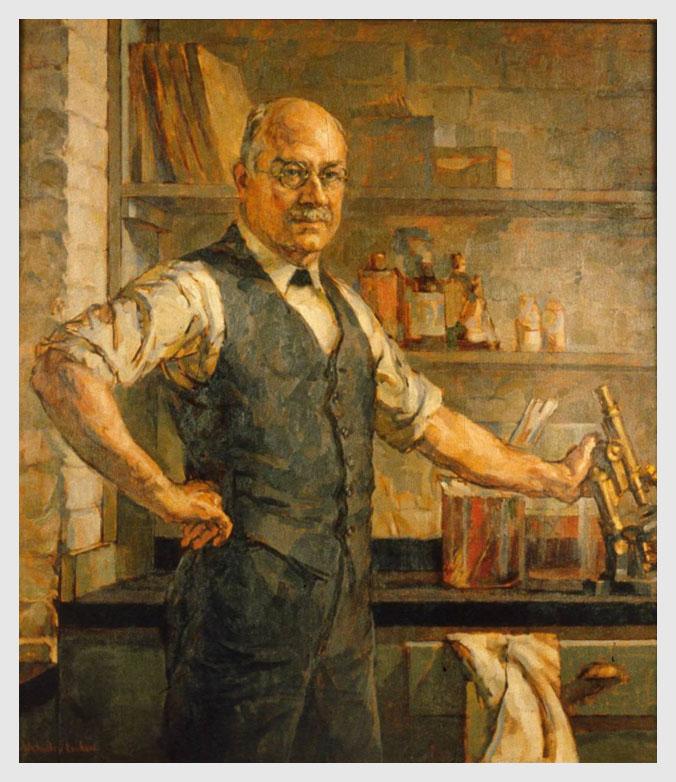

The Hygienic Laboratory was renamed the National Institute (later "Institutes") of Health in 1930 (2). Today it is the world’s premier biomedical research organization, containing not only the core Institute that once was the Hygienic Laboratory—now called the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID)—but 26 other Institutes and Centers that work globally with the nation’s and the world’s best scientists to prevent and treat virtually all human diseases. An oil portrait of Kinyoun hangs in the main administration building of NIH, Building 1, the James Shannon Building (Figure 23). In 1962, NIH celebrated its 75-year anniversary with a symposium featuring historical talks on the history of NIH, remarks about the founding of the Hygienic Laboratory, and with a newly drawn artist’s rendering of Kinyoun on the brochure’s cover. A Kinyoun Lecture Series, begun by NIAID in 1979, is among the most prestigious of NIH’s named lectures. Were he alive today, Joe Kinyoun would surely be astonished and gratified to see what his efforts produced. Surely he would be far less interested in NIH’s buildings, laboratories, equipment, and scientific techniques than in what NIH is doing, and will do in the future, to save human lives and reduce the suffering caused by diseases.

Figure 23. Painting of Joseph James Kinyoun by artist Walmsley Lenhard (1891–1966). The painting hangs with others in a series depicting each of the NIH Directors, painted by Lenhard and later artists, in Building 1 on the NIH campus (the James Shannon Building) in Bethesda, Maryland. By the time the painting was executed, Kinyoun had been dead for decades. Other than the Zeiss microscope, which Kinyoun purchased for the Hygienic Laboratory, it is not known what information Lenhard used to compose the picture. The walls and shelves do not correspond to those of the Hygienic Laboratory in either its Staten Island or District of Columbia locations. Although Kinyoun left the Hygienic Laboratory when he was 38 years old (in 1899), his face in the painting appears to have been reproduced from a photograph taken around March 1918 (Figure 1), when Kinyoun was 57 years old, thus making him appear much older than he was when he directed the laboratory.